Compassion fatigue is a relatively new concept compared to the field of nursing. While the profession of nursing originates from the mid 19th century, one of the earliest mentions of compassion fatigue is by Carla Joinson in 1992. As mental health concerns and services have become more prominent in society over time, healthcare providers are more aware of the symptoms and impact of repeated stress on people. One very well-known example of this phenomenon is the formal recognition of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in veterans starting in 1980, even though the symptoms of PTSD have been described under different names for hundreds of years (U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, 2015).

The profession of nursing sets providers up for compassion fatigue because of the inherent expectation that nurses must put their patient’s needs before their own. As nurses continue to care for higher acuity patients as the ability to prolong life improves, the prevalence of compassion fatigue may rise. Currently, the prevalence of compassion remains highly variable depending on the sampling criteria or measures utilized, ranging from 7.3% to 46% ( Cavanagh et al., 2019; van Mol, Kompanje, Benoit, Bakker, & Nijkamp, 2015; Wijdenes, Badger, & Sheppard, 2019). Individual institutions may vary in identifying or treating compassion fatigue in employees. The interventions utilized may range from employee-assistance programs designed to provide mental health services to committees dedicated to bereavement for healthcare providers.

The World Health Organization (2020) has designated 2020 as the Year of the Nurse and Midwife as part of an effort to recognize the importance of nurses, understand the challenges they face, and address the impending shortage of nine million nurses and midwives by 2030. The International Council of Nurses and Nursing Now are urging world leaders to prioritize policies to advance the nursing profession to increase the number of nurses in addition to addressing their needs so they can better care for others.

In Arizona, there are no labor laws requiring employers to provide lunch breaks for employees or vacation benefits (Arizona State Legislature, 2020). Having dedicated time during the day to unwind and refuel is important to allowing nurses to regroup and may help decrease the feeling that the workload is too intense. Taking a vacation can help nurses separate themselves from work and regain perspective. While the Affordable Care Act does require coverage for mental health services, and Arizona labor laws do require paid sick time for employees, there are still more policy interventions that can be made to benefit nurses and decrease compassion fatigue (Arizona State Legislature, 2020; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019).

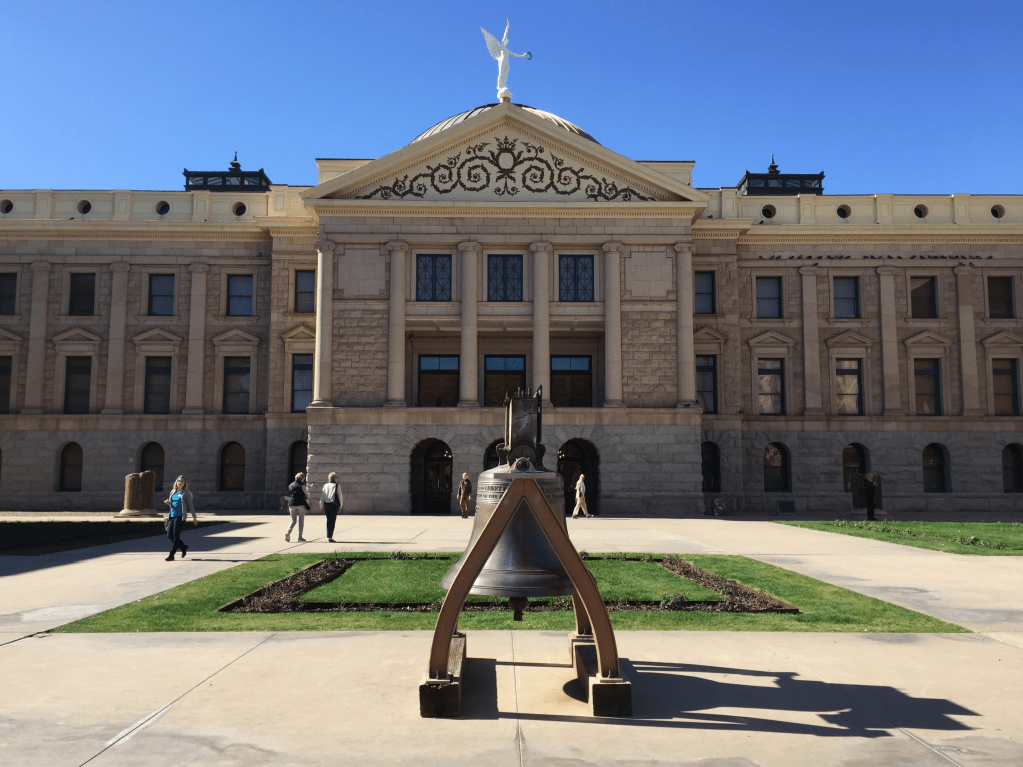

The players in the game of policymaking include policymakers, advocacy groups, and constituents. Nurses have the responsibility to advocate for themselves and the profession by speaking with policymakers about legislature that benefits healthcare workers. There is power in numbers, which is why advocacy groups, like the Arizona Nurses Association (AzNA), can be a powerful force when working with legislators. For example, during the AzNA’s Day at the Capitol, I spoke with State Representative Jennifer Pawlik from Legislative District 17 in Arizona about the benefit of HB2538. This bill seeks to prevent assaults on healthcare workers by developing a workplace violence policy to track and review all assaults, and increase the criminal classification from a misdemeanor to a felony. If this bill is passed, the hope is that the rate of workplace violence will decrease for nurses, especially those in the emergency department. By passing this bill, lawmakers would be contributing to a work environment conducive to decreasing compassion fatigue and burnout (McDermid, Mannix, & Peters, 2019).

I spoke about this bill on behalf of the nursing profession, but also for my friend. I shared his story with Representative Pawlik. My friend works in the emergency department at a Level 1 trauma center at an adult hospital. Following a particularly violent incident with a combative patient, he started taking mixed martial arts classes to defend himself in the workplace. The mere idea that healthcare workers need to go to such lengths to protect themselves from the very people they are trying to help was appalling to Representative Pawlik and she said she would vote in favor of this bill if it came to a vote.

Policies that benefit nurses benefit society because nurses are the ones providing direct patient care to our most acutely ill and vulnerable populations. Decreasing compassion fatigue will decrease burnout and stop good nurses from leaving the profession. Keeping good nurses in the profession means people will continue to receive exceptional care when they need healthcare services.

References

Arizona State Legislature. (2020). Title 23 – Labor. Retrieved from https://www.azleg.gov/arsDetail/?title=23

Cavanaugh, N., Cockett, G., Heinrich, C., Doig, L., Feist, K., Guichon, J. R., … Doig, C. J. (2019). Compassion fatigue in healthcare providers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nursing Ethics, 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733019889400

McDermid, F., Mannix, J., & Peters, K. (2019). Factors contributing to high turnover rates of emergency nurses: A review of the literature. Australian Critical Care, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2019.09.002

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2019). Does the Affordable Care Act cover individuals with mental health problems? Retrieved from https://www.hhs.gov/answers/affordable-care-act/does-the-aca-cover-individuals-with-mental-health-problems/index.html

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2015). PTSD and Vietnam veterans: A lasting issue 40 years later. Retrieved from https://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/publications/agent-orange/agent-orange-summer-2015/nvvls.asp

Van Mol, M. M., Kompanje, E. J., Benoit, D. D., Bakker, J., & Nijkamp, M. D. (2015). The prevalence of compassion fatigue and burnout among healthcare professionals in intensive care units: A systematic review. PLoS One, 10(8), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136955

Hello,

Great job on this blog and beautiful picture! So great!

I have my occurrence with nurse fatigue as well. I started off wanting to be only a pediatric nurse and, eventually, a pediatric provider. My first few years of nursing as a new grad were in a pediatric hospital. I thought I had met my dream job and count not wait to start it! I loved working with sick children in the hospital and helping them feel better, but I was not too fond of the stress of losing any one of them. My first patient that died put me over the edge.

I never had in my life experienced the death of a child, and this child was “MY” child that I took care of over the past few years. My co-workers told me I needed to go to the child’s room and see him, but I stood frozen at the door crying. I couldn’t go in. I saw him lifeless in his little hospital crib still wrapped in our old hospital blanket.

Some people told me, “It will get better over time,” and things like “you won’t react so strongly as time goes on to other deaths.” Even hearing those “words of encouragement” fatigued my mental and emotional being further.

After a couple more years and a few more child deaths, I couldn’t take it anymore. I had to leave. Unfortunately, I was never encouraged to take a vacation or any break. As a new grad, I left that job upset that I chose nursing as my life career, and I remember feeling so tired and lost. It was a tough time.

Needless to say, I am back! Though the road was long and very curvy.

I think many believe “nurse fatigue” is just working a lot of hours. While that is true, there is also mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual fatigue, too, as you mentioned about your friend. Davis (2016) says that as nurses, we are committed to our patients, but we need the additional protection of the facility in which we work. I’m wondering about not only making sure nurses have lunches and take breaks but also inducing policy that helps facilities support their nurses in other ways. For example, a quick mandatory online course on nurse fatigue (paid time of course =), or what about something to help out our new grads who are excited but often overwhelmed at how much “real life” is NOT precisely like our nursing and some who, like me, were not accustomed to dealing with the death of a patient? I just feel like there is a lot to do to aid in supporting help for nurse fatigue. I’m so happy you are blogging about this, it’s a great topic and super important!

Reference

Davis, L. K. (2016). Nurse fatigue. American Journal of Nursing, 116(12), 13.

LikeLike

Michelle,

You bring up a great point about training new nurses in the signs and symptoms of compassion fatigue and what they can do to protect themselves when it comes up. My educator and I were just discussing this need for our newly employed nurses at our hospital. I plan on implementing some of the education from the End of Life Nursing Education Consortium curriculum to address these needs!

LikeLike

In my opinion, compassion fatigue in nursing is always a timely topic to discuss! I always chuckle somewhat when I think of this topic because even the airlines have this figured out when they say, ‘in case of emergency, please apply your mask first and then apply the mask to those around you’. Airlines recognize that in times of emergency (or crisis) we must prepare ourselves first!

Compassion fatigue is often fueled by burnout which can be defined as “a state of mental and/or physical exhaustion caused by prolonged exposure to chronic and excessive stress” which can lead to emotional exhaustion, detachment, poor sense of accomplishment and lack of effectiveness (Koh et al., 2020). I know that most of us are perhaps aware of this phenomenon and maybe even understand some ways to combat it yet there remains a gap in practice. Processes of self-awareness and reflection help to build resiliency as we struggle, change our mindset, then learn to adapt (Koh et al., 2020). Research has shown that outside emotional support from our peers and supervisors plays a vital role in our ability to build resiliency (Chang, 2018).

As a hospice nurse of almost 15 years, I can confidently stand before you and testify to this truth. It is ABSOLUTELY crucial to process your struggles with your peers from work in order to build resiliency. Not only does it help you in the short term of simply being able to get through your day, but the literature is showing this is helpful in the long run too. For clinicians who have spent greater than 10 years in specialties where burnout is very plausible displayed abilities to overcome burnout through their personal coping mechanisms along with leadership who display qualities of genuineness and compassion (Koh et al., 2020).

As future leaders in our own practices, I think it is important for us to care for our peers by helping them to cope, helping them to build short term and long-term resiliency. This will not only make for a supportive working environment but help to address staffing shortages by maintaining higher rates of retention.

References

Chang, W. (2018). How social support affects the ability of clinical nursing personnel to cope with death. Applied

Nursing Research, 44, 25-32. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2018.09.005

Koh, M., Hum, A., Khoo, H.S., Ho, A., Chong, P.H., Ong, W.Y., … Yong, W.C. (2020). Burnout and resilience after a

decade in palliative care: What survivors have to teach us. A qualitative study of palliative care clinicians with

more than 10 years of experience. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 59(1), 105-115. doi:

10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.08.008

LikeLike