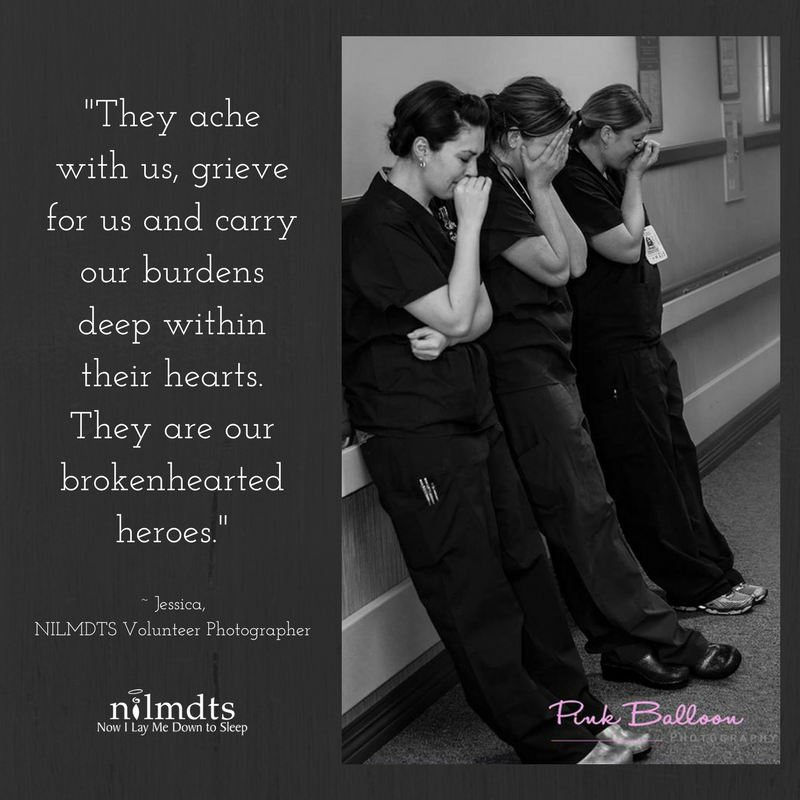

How do people become brokenhearted? Some might say broken hearts result from the dissolution of a relationship. Others might suggest that broken hearts are a consequence of traumatic loss. But every nurse I have ever met has had some form of a broken heart as a result of compassion fatigue.

Compassion fatigue. A term that is used by many, but not well understood or quantified. Each nurse’s journey dealing with compassion fatigue looks different, which is why it is such a nebulous concept to fight against.

As a newly graduated pediatric hematology and oncology nurse, I had never attended a funeral before. The only people I had ever grieved were my grandparents in China, who I had seen a handful of times in my life. I had volunteered at a pediatric oncology camp for one summer, but everyone at the camp was healthy and not actively going through treatment. Because I was so unfamiliar with death, I was wholly unprepared to deal with the grief and tragedy I saw every day in my practice.

When I started training on the floor, I met a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia named Jack*. Jack was the sweetest child and he was so willing to help me out as I fumbled around with cords and lines, trying to figure out how to use the machines that were monitoring his medications and vital signs. He would hold out his arm for his blood pressure, he would take his medications without a fight, and he loved spending time with his parents.

At the same time he was in my hospital, one of my campers, Carla*, relapsed for a second time with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. She was admitted to another hospital for a bone marrow transplant. Her father posted her daily updates on their CaringBridge online journal for all her friends and family members to read. As she progressed through her bone marrow transplant process, I progressed through my training as a new grad nurse.

Jack and Carla died within a week of each other. Jack died from his cancer and Carla died from complications related to her bone marrow transplant. Following their deaths, I had to figure out how to deal with this grief I had never really experienced before. I attended my first funerals and had to learn how to occupy that space as a nurse grieving for a patient.

In the five years since I started my nursing career, I have cared for hundreds of children fighting cancer; yet I still carry Jack and Carla with me as I care for my patients. I still feel disenfranchised grief when one of my patients dies. I still mourn their loss of function, loss of normalcy, or loss of life.

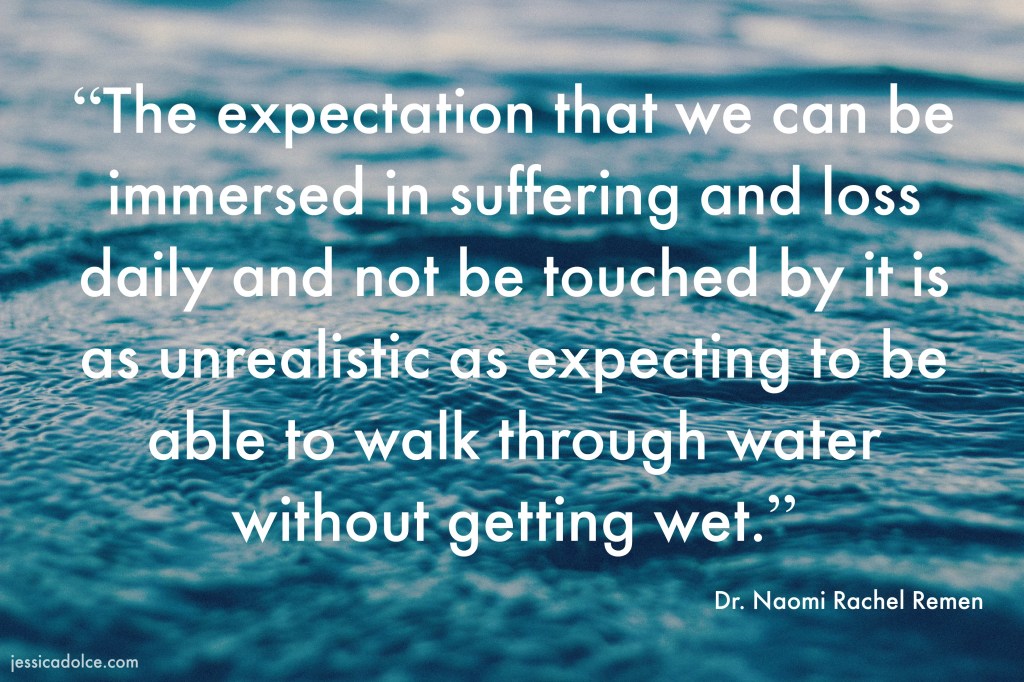

Nurses are surrounded by distress and resiliency, joy and suffering, and grief every day in our practice. Compassion fatigue is the emotional and physical exhaustion experienced by people frequently exposed to suffering, and can result in secondary trauma1. When nurses experience compassion fatigue, they may experience insomnia, depression, anxiety, difficulty concentrating, overwhelming grief or despair about patients, or feeling hopeless or powerless. This can lead to burnout and nurses leaving their chosen population or the profession entirely. This is a coping mechanism, a way to protect themselves from the pain inherent in any healthcare profession.

I have felt the effects of compassion fatigue myself. I have been overwhelmed by the prospect of losing a patient. I have driven home with tears streaming down my face because I could not express my emotions at work. I have contemplated leaving my profession because of the overwhelming grief. But I carry the patients I have lost close to my heart. I use the joy I find in my work every day to provide a breath of optimism admits all the nausea, pain, and grief. By continuing to find the joy in my career, I am able to sustain my practice as a pediatric oncology nurse. But not everyone is able to find their own practices to combat compassion fatigue. I have had so many friends switch from one hospital to another, switch from the inpatient setting to the clinic, or leaving nursing entirely, hoping to find a reprieve from their compassion fatigue.

In Arizona, there are no universal policies in place to combat compassion fatigue. While 30 minute lunches and breaks are mandated by labor laws, they are not enforced sufficiently in a profession known for putting patients first. If the needs of the patients require a nurse to skip a lunch and the hospital is unable to provide respite time for the nurse, then that nurse forgoes lunch to put the patient first.

Each hospital and outpatient facility has their unique ways of preventing compassion fatigue in nurses. Whether that involves an Employee Assistance Program for mental health services, resource nurses to provide an extra set of hands, or scheduled breaks throughout the day, employers have many resources available. However, the lack of a state-wide policy to prevent and treat compassion fatigue leaves many nurses struggling alone as they try to care for themselves and patients.

If we do not come up with ways to combat compassion fatigue on a state-wide level, we will continue to lose exceptional nurses from the profession. It is in our nature as human beings to turn away from pain. When the source of that pain is the repeated trauma of working with acutely ill patients, then there needs to be policies built in place to help people recover from and prevent compassion fatigue.

*names have been changed to protect patient privacy

References

- Compassion Fatigue Awareness Project (2017). Did you know? Retrieved from https://www.compassionfatigue.org/

Winnie,

Thank you so much for sharing your personal experience and making an effort to bring this topic to light. I have been a registered nurse for five years and I have been lucky to be in the float pool of a local level one trauma hospital. This has allowed me to grow personally and professionally. I have been challenged many times as a person working with individuals with different beliefs, values and attitudes. I have also been challenged professionally by learning how to delivery care to different patient populations, be knowledgeable. Three years ago, I decided to take my career in another direction and became a critical care float nurse. It has been an amazing experience, but also a very challenging one.

It is amazing to care for a human being that is struggling to stay alive and see and know that your care has allowed them to live another day, to recovery and share more moments with their loved ones. That makes what I do so rewarding. However, I cannot tell you how much death I have seen in my short time as an ICU nurse. There are times we try our best and our best isn’t enough. You are absolute right; we are all challenged with compassion fatigue and it is challenging dealing with those feelings. I can also say it is difficult not being able to share those feelings at times because you fear someone else may not understand. Nurses don’t have a typical job like most people do. We go through happiness, fatigue, emotional and physical distress all in one 12-hour shift. I always hear people say, “leave work at work, go home and relax” and although I try, sometimes it is easier said than done.

Reading your blog made me want to learn more about this topic. I realize that compassion fatigue affects 16% to 39% of registered nurses. I understand all nurses can experience this; however, I was surprised to learn that nurses working in emergency, oncology, hospice, and pediatric settings have a highest risk (Durning, 2016). I understand first-hand how stressful and depressing critical care nursing can be therefore I thought it would be top of the list. I found an interesting article that defines compassion fatigue as experienced burnout in the face of intense work demands and secondary traumatic stress arising from workplace exposure to patients experiencing severe trauma (Kelly & Todd, 2017). According to Kelly and Todd (2017) compassion fatigue can be counterbalanced by compassion satisfaction such as pleasure and gratitude a caregiver received from his or her work.

I imagined this would be more prominent in nurses who have been doing this for a long time. Interestingly, younger, inexperienced nurses have higher risk for low compassion satisfaction and high compassion fatigue (Kelly & Todd, 2017). This also contributes to nursing retention problems with about 20% of nurses leaving their positions in the first year and many leaving the nursing profession altogether (Kelly & Todd, 2017). I look forward to following your blog and learning more about this topic.

References

Durning, V. M. (2016). Compassion fatigue: How nurses care for themselves. Retrieved from https://www.oncnursingnews.com/publications/oncology-nurse/2016/april-2016/compassion-fatigue-how-nurses-can-care-for-themselves

Kelly, L., & Todd, M. (2017). Compassion fatigue and the healthy work environment. AACN Advanced Critical Care, 28(4), 351-358. Doi: 10.4037/aacnacc2017283

LikeLike

I’m not surprised that the article by Kelly and Todd (2017) found that newly graduated nurses are at higher risk for compassion fatigue. I think this statistic is related to the fact that our society does not discuss death very often. When we do discuss death, it is at sanctioned events like a funeral, and it is quickly compartmentalized. Newly graduated nurse may have never attended a funeral or known someone who passed away, so dealing with the new experience of a patient dying while they are trying to figure out how to do basic nursing tasks can be incredibly traumatic.

As nurses gain experience, they also gain coping skills related to the ability to manage their disenfranchised grief and compassion fatigue. But they have to have the opportunity to learn those skills as a new nurse first. Right now, I see too many new grad nurses wholly unprepared for the realities of inpatient nursing. They do not have the policies in place to give them the training, the time, and the space to learn these coping skills before being overwhelmed by their compassion fatigue. Once they are overwhelmed, they turn to survival mode to find any way out of the trauma, whether that is leaving for a different unit or hospital or leaving the profession altogether. This is why we need policy change: to allow nurses the space and grace of being human and learning how to cope with or prevent compassion fatigue.

References

Kelly, L., & Todd, M. (2017). Compassion fatigue and the healthy work environment. AACN Advanced Critical Care, 28(4), 351-358. doi: 10.4037/aacnacc2017283

LikeLike

Grieving tragedy is a complex and unique process and I appreciate your post as an excellent description to convey the experience of grief within the context of compassion fatigue in the health care professional. Health care literature has identified compassion fatigue as prevalent and measurable, as well as identified factors that impact the best outcomes for people who work in health care to address compassion fatigue (The Joint Commission, 2019; Penix et al., 2019).

A leading health care accreditation agency, the Joint Commission, has published Quick Safety Issue 50 regarding compassion fatigue among nurses, including current studies and literature (2019). The Joint Commission recommends the use of the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) measurable tools for health care organization to provide the health care providers within their organizations to evaluate the status of compassion fatigue within their institution (NAM).

The Joint Commission emphasizes preventing compassion fatigue by promoting resiliency, or “the process of personal protection from burnout” (2019). In Quick Safety Issue 50, the Joint Commission calls for organizations to intervene by promoting resilience. They list the findings of a study by Cameron and Brownie in 2010 showing factors that promote resilience, which includes “experience, amount of satisfaction attained, positive attitude or sense of faith, feeling of making a difference, leadership strategies, such as debriefing, validation and self-reflection, support from colleagues, mentors and teams, insight in ability to recognize stressors, and maintaining work-life balance” (2019).

Health care organizations have leading health care accreditation agencies recommending they intervene to prevent compassion fatigue, the literature has an abundance of evidence on prevalence and effective interventions, and the National Academy of Medicine has valid and reliable surveys that can be used to evaluate current levels of compassion fatigue (2019). Unfortunately. the Joint Commission reports data has shown half of respondents work at an organization that was not effectively addressing compassion fatigue (2019). In the health care field, it remains to be seen what intervention is going to be implemented to help health care organizations address compassion fatigue effectively. It appears collaboration to address compassion fatigue with health policy is an important strategy for health care institutions to utilize.

Cameron F and Brownie S. Enhancing resilience in registered aged care nurses. Australian Journal on Ageing, 2010;29(2):66-71.

National Academy of Medicine. Valid and Reliable Survey Instruments to Measure Burnout, Well-Being, and Other Work-Related Dimensions. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine.

Penix, E., Kim, P., Wilk, J., & Adler, A. (2019). Secondary traumatic stress in deployed healthcare staff. Psychological Trauma : Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 11(1), 1-9.

The Joint Commission (2019) Quick safety issue 50: Developing resilience to combat nurse burnout. Retrieved from https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/news-and-multimedia/newsletters/newsletters/quick-safety/quick-safety-50-developing-resilience-to-combat-nurse-burnout/

LikeLike

Winnie, compassion fatigue is such an important topic to discuss as it affects all nurses, no matter what specialty we work in. Dr. Charles Figley, a professor at Tulane University, defined compassion fatigue as “a state experienced by those helping people or animals in distress; it is an extreme state of tension and preoccupation with the suffering of those being helped to the degree that it can create a secondary traumatic stress for the helper.” It is in our DNA as nurses to selflessly give all of ourselves to the people we care for. As nurses and as human beings, we care about our patients. We feel their pain and suffering. We want them to get better. We worry. Sometimes we can’t sleep at night hoping they are doing OK. We wonder if there was something more we could have done. Constantly surrounded by human distress and suffering, mental and physical exhaustion sets in, resulting in secondary trauma that manifests itself as anxiety, depression, insomnia, feelings of hopelessness, or self-destructive behaviors. Emotionally and physically exhausted, and with complete focus on others, we often don’t even recognize that we are suffering from compassion fatigue.

Being kind to ourselves, enhancing our awareness with education, accepting where we are on our path at all times, exchanging information and feelings with people who can validate us, listening to others who are suffering, clarifying our personal boundaries, expressing our needs verbally, supporting each other, and take positive action to change our environment are some of the steps we can take on our path to wellness (Compassion Fatigue Awareness Project, 2017)

References

Compassion Fatigue Awareness Project (2017). The path to wellness. Retrieved from: https://www.compassionfatigue.org/pages/pathtowellness.html

LikeLike